Court Approves Non-Statutory Three-Second Rule

An Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals tailgating opinion contrary to its decision in a similar case just 19 months earlier highlights the court’s tendency to publish as precedent only those decisions favorable to the prosecution. Published cases have the effect of precedent that governs courts’ disposition of future cases.

This precedent gives police a basis to stop almost any driver on suspicion of following too closely.

The court concluded a narcotics officer’s use of a three-second “rule of thumb” for following too closely provided reasonable suspicion to stop the driver. The officer was parked in the median of I-40 when he estimated a minivan — traveling 65 or 70 mph — passed within one second of a semi-truck ahead of the minivan.

The May 1, 2015 decision in Oklahoma v Zungali, 2015 OK CR8 cited federal 10th Circuit Court cases that said a non-statutory two-second tailgating rule could in some circumstances provide reasonable suspicion for a traffic stop.

The decision is bizarre in its own right. To make matters worse, in an unpublished Oct 2. 2013 decision the Oklahoma criminal appeals court had upheld a district court decision to suppress evidence seized after a traffic stop for following too closely. In that case, an officer had relied on a more lenient two-second rule to determine a “reasonable and prudent” distance between vehicles. (Oklahoma v. Uriel Lopez, McIntosh OK — CF-2011-00300A)

Reason, Prudence and Following Too Close

OCCA May 2015:

“We find that Agent Wall’s use of a three-second rule of thumb together with his calculation and observation of less than a one second interval in this case provided the minimal level of objective justification required for reasonable suspicion justifying a traffic stop.”

OCCA Oct. 2013:

“[T]he district court concluded that the use of the two-second rule alone, as a general ‘rule of thumb’ to determine that the offense had been committed was subjective and not an objective interpretation of the statute. Based on this the district court granted the motion to suppress and quash the evidence. We find that the district court’s conclusion that the trooper did not have a reasonable suspicion that a violation of law had occurred was not an abuse of discretion.”

Oklahoma law does not say exactly how closely a driver can follow another vehicle. Instead, the law says a driver “must not follow another vehicle more closely than is reasonable and prudent, having due regard for the speed of such vehicles and the traffic upon and the condition of the highway.” (Okla. Stat. tit. 47 § 11-310(a))

The open-ended language leaves drivers, cops and courts to determine a “reasonable and prudent” distance for following another vehicle.

In the 2013 decision, the criminal appeals court noted that the district court heeded the higher court’s admonishments “not to enlarge the meaning of words included in the statute to create a crime that is not defined in the statute.”

At that time, the Oklahoma appeals court affirmed a district court’s conclusion that the non-statutory two-second rule made it impossible for a “reasonable person to understand the prohibited conduct.”

Less than two years later, the appeals court was more concerned about a narcotics interdiction officer’s latitude to claim reasonable suspicion than about Oklahoma drivers’ need to know how closely one can legally follow another vehicle.

In both cases, the officers had alluded to “numerous” sources as the basis for a two-second rule or a three-second rule.

In 2013, an officer testified that “numerous drivers safety handbooks and websites” advocate a two second rule. In 2015 an officer said “numerous studies as well as the Oklahoma Drivers Manual” advocate a three-second rule.

It is worth noting that none of the tailgating precedents directly addressed traffic violations. They were all drug war cases. In each of the tediously argued appeals, the case before the court was whether an officer had reasonable suspicion to initiate a traffic stop that led to felony drug charges.

With more vehicles than ever now sporting collision avoidance braking systems, we doubt the safe following distance for Oklahoma drivers increased by 50 percent in two year’s time.

If any of the drivers had simply been cited for an infraction, it is safe to say a traffic ticket attorney might have successfully challenged the citations – unless the officer presented more evidence than a quick glance that singled out one vehicle from a flow of traffic.

The narcotics officer who initiated the traffic stop on I-40 said he was unable to “even count a second” between the minivan and a semi-truck ahead of it. Yet during the time traffic sped past the narcotics cop parked in the median of I-40 at 65 or 70 mph, he was able to determine the minivan appeared to be a rental vehicle from Florida.

One wonders if one can accurately measure one second of following distance while simultaneously reading license plates and profiling vehicles as out-of-state rentals.

Made-up Law Does Not Tailgate Traffic Science

Now, there’s probably a good reason some district courts and a few federal courts have wanted more than a quick glance from an officer to establish that a driver was tailgating. To our knowledge, no Oklahoma legislative effort has reviewed the science behind a two-second rule or a three-second rule.

The nexus between the defensive driving suggestions and traffic engineering science is elusive.

German law mandates a 0.9 second space between vehicles, but studies suggest two out of five vehicles in Germany follow more closely. Our everyday experience on U.S. highways suggests following distances of under two seconds are often the norm, with much closer spacing in congested high-speed traffic.

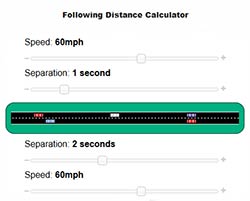

How much would traffic back up each day if every driver added two or three seconds of space between the car ahead? How much distance does a two-second rule require?

Do the math. According to Wikipedia, the average family car these days is 189 inches long – 15.75 feet. Traveling 60 mph, a car travels a mile a minute – 5,280 feet. That’s 88 feet per second.

If you follow three car lengths behind another vehicle at 60 mph, that’s about a half second. A car traveling one second (88 feet) behind another car at 60mph would be more than five and half car lengths behind. (88/15.75=5.59)

A car obeying a two-second rule would be 11 car lengths behind. A three-second rule puts a vehicle almost 17 car lengths behind the next car.

Now consider what a three-second rule would do to congested traffic moving at 60mph through a busy downtown Interstate.

With two car lengths between vehicles traveling 60 mph, a mile of highway can accommodate 112 vehicles. With three seconds of distance, that same mile of highway can accommodate 19 vehicles.

Spaced two car lengths apart at 60 mph, 6,705 cars an hour can pass through a mile of highway in an hour. With one second following distance, the hourly capacity decreases to 3,053 vehicles.

With three seconds distance between each car, the number drops to 1,132. That would leave 5,572 drivers waiting until the defensive drivers clear the mile of highway with 3 seconds spacing between them.

VEHICLE SPACING AT 60 MPH |

|||

| Following distance | Car lengths | Cars per mile | Cars per hour |

| 2 car lengths | 2 | 112 | 6,705 |

| 3 car lengths | 3 | 84 | 5,029 |

| 1 second | 5.59 | 51 | 3,053 |

| 2 seconds | 11.17 | 28 | 1,652 |

| 3 seconds | 16.76 | 19 | 1,132 |

THE MATH: |

|||

| Feet per second @ 60mph: | 60/5,280 = 88 | ||

| Car lengths of following distance: | (feet per second x number of seconds)/15.75 | ||

| Cars per mile: | 5,280/(car lengths + one car) | ||

| Cars per hour: | cars per mile X 60 minutes | ||

Our experience and a review of Google Maps satellite imagery such as the picture on this page suggest two-car-length spacing is routine in even slightly dense traffic. On a busy but otherwise not congested highway, drivers are more likely to spread out with one-second or two-second spacing between them. Three-second spacing would seem to require a deliberate effort to wait until a vehicle ahead moves on.

Yet appeals courts, determined for whatever reason to accommodate the predilections of drug enforcement cops, have crafted far-fetched notions about what is reasonable with no consideration of traffic engineering or common sense about what are likely the judges’ everyday driving habits. In essence, they crafted judicial traffic law.

Not Following Too Closely the Bill of Rights

Oklahoma’s criminal appeals court has now allowed police to tout this obvious fiction as the basis for reasonable suspicion. Under this precedent, police can claim to have reasonable suspicion of almost any driver who drives like almost every other driver on the road.

We suspect many drug cases that start with traffic stops do not originate with an officer’s casual observation poor driving. We hold reasonable suspicions that drug warriors often fabricate pretexts for traffic stops after targeting an individual driver based on profiling, tips or warrantless surveillance.

Our suspicions are informed reports in 2013 that the U.S. DOJ’s Drug Enforcement Agency’s Special Operations Division training in a tactic known as parallel construction to hide the how criminal investigations are initiated.

Reuters news agency reviewed documents revealing how the DEA distributes information from intelligence intercepts, wiretaps, informants and a massive collection of telephone records then instructs agents to cover up their sources.

The parallel construction game deprives defendants of a Fifth Amendment right to due process and a Sixth Amendment right to confront witnesses against them. Parallel construction allows federal agents to hide — even from prosecutors — evidence that might otherwise help defendants, often called “Brady material.” (See Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963))

Some courts are apparently all too willing to go along with the charade. This precedent gives cops a green light to stop anybody on a pretext, with nary a concern for exposing their true investigative methods — no matter how illegal, repugnant or unreliable is the true source of their suspicion.

We would prefer that Oklahoma courts recognize their own precedent. Consistency is the foundation of a system of laws. When one set of decisions goes unpublished while contrary decisions by the same court are published as precedent, trust in the rule of law is eroded.

Strategy Session: Tulsa Traffic Ticket Attorney

For a person facing charges, contradictions among a court’s various decisions are more of a practical concern. Reasonable and prudent drivers hauled into court because they did not obey a two-second rule need a skilled Oklahoma traffic citation attorney to tell a court the difference between defensive driving recommendations and Oklahoma law.

When the case is more serious and police have used ambiguous laws to construct a pretext for a drug arrest, an Oklahoma criminal defense attorney’s role is all the more vital.

Only a careful examination of every detail of your case can reveal the best defense strategy.

To schedule your initial strategy session with a Tulsa criminal lawyer about a traffic citation or about a major drug felony, contact Wirth Law Office at 918-879-1681 or send your question using the e-mail form at the top of this page.